[ad_1]

Victor Sharrah had always had sharp vision. But one life-altering day in November 2020, he noticed out of the blue that people’s faces around him looked demonic.

Their ears, noses and mouths were stretched back, and there were deep grooves in their foreheads, cheeks and chins.

“My first thought was I woke up in a demon world,” said Sharrah, 59, of Clarksville, Tennessee. “You can’t imagine how scary it was.”

Someone he knew taught visually impaired people and suggested he might have prosopometamorphopsia, or PMO. The extremely rare neurological disorder of perception causes faces to appear distorted in shape, size, texture or color. Sharrah felt the symptoms were a match, and he was formally diagnosed last year.

The distortions appear only when he sees people in person — not in photographs or through computer screens.

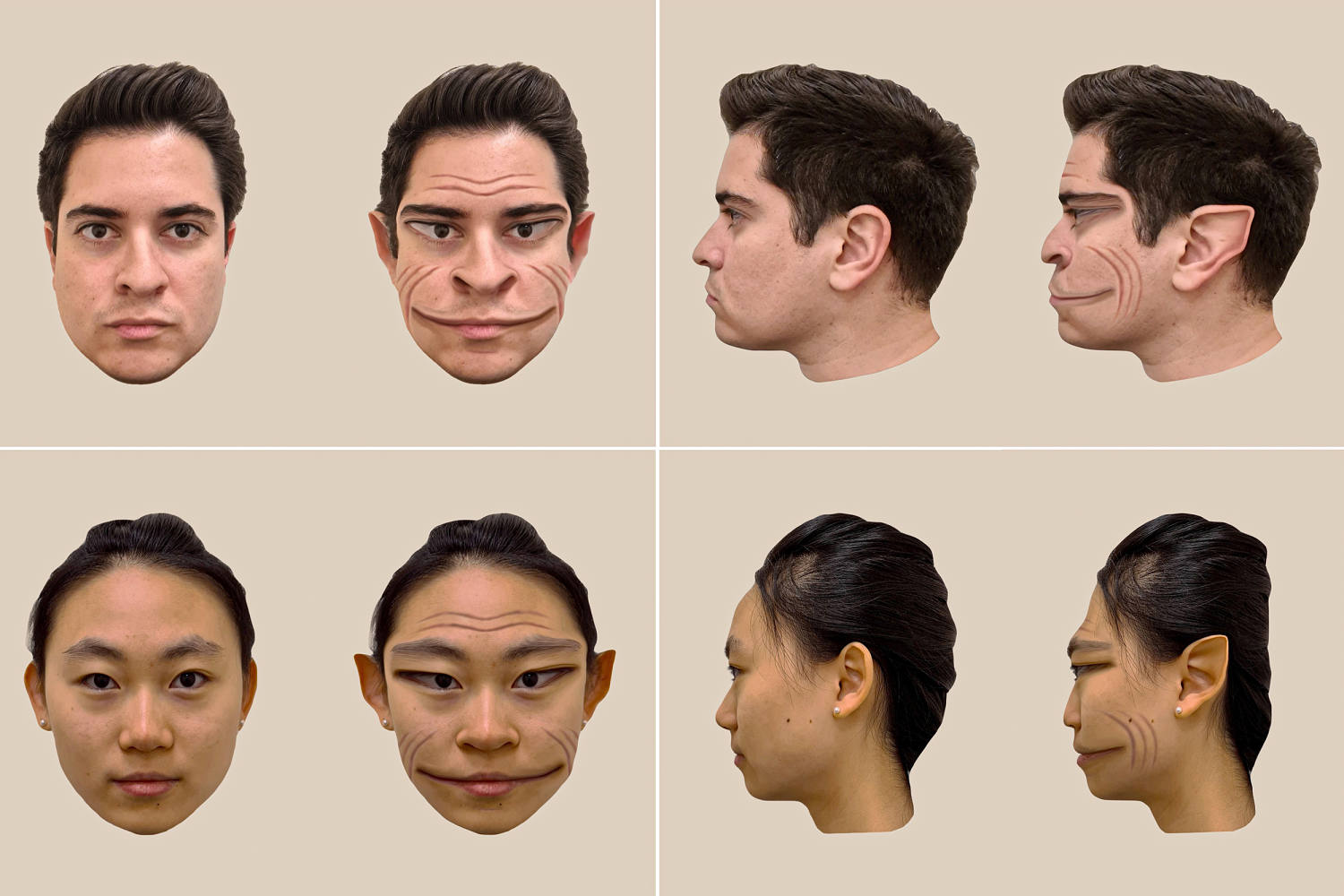

That gave scientists an opportunity to visualize what the warped faces look like for a person with PMO, something they had never been able to do before. Researchers at Dartmouth College created a digital representation of what Sharrah has been experiencing. The resulting images were published Thursday in The Lancet.

To create the visuals, the researchers asked Sharrah to describe the differences between photographs of people’s faces and the real-life people standing in front of him. The researchers then used image-editing software to modify the pictures to match Sharrah’s description.

PMO symptoms often resolve after a few days or weeks, though in some cases they can linger for years. Sharrah said he still sees demonic faces.

There are fewer than 100 published case reports of PMO. Researchers suspect it is caused by dysfunction in the brain network that handles facial processing, though they don’t fully understand what triggers the condition. Some cases have been linked to head trauma, stroke, epilepsy or migraines, but other people have PMO without obvious structural changes in their brains.

The researchers offered two possible triggers for Sharrah’s case. First, he had carbon monoxide poisoning four months before his PMO symptoms started. Second, he endured a significant head injury at age 43: While he was trying to unjam the handle on his trailer, Sharrah fell backward and hit his head on concrete. According to the study, MRI scans showed a lesion on the left side of his brain.

The study’s lead author, Antônio Mello, a Ph.D. student who works in Dartmouth’s Social Perception Lab, said other people have reached out the lab with PMO symptoms that differ significantly from Sharrah’s.

Some people “have seen face distortions since they remember, since they were a child,” Mello said. “For them at least, it’s impossible to find a single event that was responsible.”

Researchers even suspect the condition may be underreported.

“We’re hearing from somebody new every week or two” who describes symptoms consistent with PMO, said Brad Duchaine, a co-author of the study and principal investigator of the Social Perception Lab.

He added that some patients he’s worked with in the lab “don’t tell anybody or tell very few people about it, because they’re afraid of what others are going to think.”

In addition, Mello said, many doctors aren’t aware of PMO and may misdiagnose people with mental health disorders, instead. As a result, some PMO patients have been prescribed medications for schizophrenia or psychosis, which aren’t appropriate for their condition, he said.

A key difference between PMO and psychological disorders, Mello said, is that people with PMO “don’t think that the world is really distorted — they just realize that there is something different with their vision.”

While there is some overlap in the symptoms that various PMO patients describe, there is also a good deal of variation, Duchaine said. So the images in the case study may be unique to Sharrah’s experience.

Duchaine said he has spoken to people who see drooping faces, as well as a woman who sees two faces when she looks at someone — one in front of the other. Another woman he spoke to recently sees “witch-like” faces with long noses and pointy ears, Duchaine said.

“The first time it happened, she was on a beach in Jamaica and was looking at two women who were standing in the water. They had this witch-like appearance at one moment, and then they didn’t a while later,” he said.

A case study published in 2018 described a 68-year-old woman who developed PMO after a stroke. Although her neurological and eye exams were normal, she reported that people’s left eyes moved upward and to the side when she saw them in person or watched them on television. Her own face looked normal to her in a mirror, though.

“On TV, she saw people having half of their face distorted, and it was the left half. Her stroke was on the left, as well,” said a co-author of that case study, Dr. Nada El Husseini, an associate professor of neurology at Duke University School of Medicine.

Husseini said it’s possible that PMO symptoms are worse when people look at moving faces, which could explain why some people don’t notice facial distortion in photographs.

Sharrah said that’s consistent with his experience.

“When I’m looking at a person, that face is moving, it’s talking, it’s gesturing. So it really increases the effect of it,” he said.

Sharrah said he has found a few ways to cope with his condition. He lives with a roommate and her two kids, which he said has been helpful, because he’s used to having people around, so he isn’t as spooked when he sees new faces in public. For reasons that aren’t clear to researchers, Sharrah also finds that green light alleviates his symptoms, so he sometimes wears glasses with green-tinted lenses when he’s in crowds.

He wants others to know they can manage the condition, as well.

“I came so close to having myself institutionalized,” Sharrah said. “If I can help anybody from the trauma that I experienced with it and keep people from being institutionalized and put on drugs because of it, that’s my No. 1 goal.”