[ad_1]

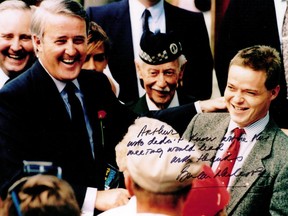

We were an unlikely pair. I’d always voted Liberal. Then, for five years, I helped him work on his memoirs — an extraordinary partnership and privilege.

Article content

I loved Brian Mulroney. His leadership. His political skill. His determination. His delicious sense of fun and friendship that, both inside and outside of politics, defined the man behind the headlines.

I loved these and so much more that I grew to know so well during the five years I served as the assistant on his memoirs.

Article content

I hardly knew Mr. Mulroney when he invited me — over lunch in Montreal one day in December 2002 — to serve as his assistant as he began turning remembrances into writing. I had contacted him, asking for an interview, as a reporter from the Kingston Whig-Standard, months earlier. Together with my interview request, and with genuine interest, I also inquired why he had not yet written his story.

Advertisement 2

Article content

And then my mother-in-law intervened.

Only a week or so after I mailed my letter to Mr. Mulroney, Mary Bogle of Toronto called me with excitement. “Guess who I saw at (Pearson) airport tonight,” she said. “It was Brian Mulroney and I gave him a piece of my mind for not giving you an interview.”

My life passed before me, fearing that she’d forever ended any chance I would ever have of interviewing the 18th prime minister of Canada. I asked Mary what Mr. Mulroney’s reply had been.

“He said to tell you that now he has met your in-laws, he’ll call you,” she replied.

And sure enough, when I arrived at the Whig-Standard the next morning, the message light on my phone was already flashing. More than 20 years later, I can still recite Brian Mulroney’s message from memory.

“Arthur,” that deep baritone voice announced, “it’s Brian Mulroney. I’m calling at the behest of my new best friends, your in-laws. Let’s talk.”

And that is how I ended up assisting a Canadian prime minister with his memoirs.

We were an unlikely pair. Up until then, I’d always voted Liberal (except for the time I marked my ballot for Bob Rae’s Ontario NDP in 1995). I was hardly a Tory partisan.

Advertisement 3

Article content

“Arthur, you f–king Liberal,” he said to me with a giggle, his voice nonetheless shaky and faint during a call he made from the ICU in 2005 as he faced a life-threatening illness, “how would you like to be your friend Jean Chrétien’s memoirs assistant about now?”

The call came during particularly damning testimony for his nemesis, Chrétien, during the Gomery Inquiry into the Liberals’ sponsorship program. In spite of his own illness, Mr. Mulroney was somehow still able to tease me about my Liberal voting record. I loved him for making the call.

Over almost two full years, I had reviewed his massive archival collection at Library and Archives Canada. More than 3,000 boxes in all.

And on page after page, particularly those documents involving his youth, I truly got to know Brian Mulroney. In the silence of my archives’ office in Ottawa, I marvelled, day after day, at the young man from nowhere who would become prime minister.

“With regard to our telephone conversation of yesterday afternoon … ” he started a telegram to Prime Minister John Diefenbaker when he was all of 21 years of age. How many university students spend part of their day advising the leader of their country? Well, that was the Brian Mulroney I started to get to know.

Advertisement 4

Article content

But there were also the personal moments. With great emotion, he called me one night to say he’d finally written the passage about the death of his father, Ben Mulroney, in early 1965. Though it was late, he wanted my opinion on what he’d written.

He read me his words.

“In the evenings I would take him in my arms like a child — he was losing weight very quickly — and carry him downstairs to the living room so he could watch TV and tune in to the CBC nightly news,” he wrote. “In those days the lead announcer was Earl Cameron, who always concluded his newscast with the words, ‘This is Earl Cameron saying good night from Toronto’ and my dad unfailingly replied with a smile, ‘Good night, Earl.’ He continued to do this right to the end, which came on February 16, 1965. He was sixty-one years old.”

“Should we make any changes?” he asked me quietly.

“Sir, not one,” I replied.

A year later, he was the first person to call me when my own father died. He gave me a talk, telling me how my life had now changed forever. And that my responsibility was to honour my father’s memory. Mr. Mulroney pulled no punches during that unsolicited call, talking me through a difficult time. Having read his account of his own father’s death scant months before, I felt very close to the former prime minister that sad day.

Advertisement 5

Article content

But the work of preparing a prime ministerial memoir before history continued. As we moved into his public career, Mr. Mulroney had me prepare research packs in chronological form that contained the primary sourced documentation from his archive, quotes from the private journal he kept while prime minister, along with press reports of the day. The two of us used these packs to guide us as we started the long process of tape-recorded interviews that formed the foundation of the book.

These interview sessions, which always took place in his study at his Westmount home, lasted as many as four days straight. We’d work for seven or eight hours as he orally crafted what would become a written narrative. “Arthur,” he’d always say when I’d start to pack up the recording equipment and papers, “we did the Lord’s work today.”

But what I grew to enjoy most were our personal conversations, which occurred when the work was done. Mr. Mulroney would pull his chair back and we would simply talk, often for hours. We’d discuss our wives and families, the politics of the day and more. Once, we even watched a replay in full of that day’s Question Period from the House of Commons. It was, for me, a dream come true to have had these moments with a prime minister of my country.

Advertisement 6

Article content

While I was never his friend (he was always the boss and the former prime minister), I felt I got to know him most these late afternoons.

That is how I remember him today. His legs up on the coffee table in his study, Irish blarney on full display, and me loving every second of his performances to me, an audience of one.

As he did for millions while campaigning, Mr. Mulroney held me in his spell each time. Often the crowds he described became larger and larger as the story continued, but that didn’t matter to me. Through him, and our private conversations, I too was soon in the arena alongside him as together we faced in triumph the mighty Grits of old.

And then he’d walk me to the door of his Montreal home, ask me to pass along his regards to my wife, and I’d drive back to Kingston. And I’d think then, as I do today upon learning of his death, how privileged I am to have known and loved this remarkable Canadian.

Arthur Milnes of Kingston, a public historian and political speechwriter, served as the memoirs’ assistant to Brian Mulroney for five years during the early 2000s. He now serves as the in-house historian at the Frontenac Club Hotel.

Recommended from Editorial

-

Former prime minister Brian Mulroney dead at 84

-

Preston Manning: The humanity of Brian Mulroney has been lost in Canadian politics

Article content