[ad_1]

Suppose that when your first child turned nine, a visionary billionaire whom you’d never met chose her to join the first permanent human settlement on Mars. Unbeknown to you, she had signed herself up for the mission because she loves outer space, and, besides, all of her friends have signed up. She begs you to let her go.

You hear her desire, so before saying no, you agree at least to learn more. You learn that the reason they’re recruiting children is because they will better adapt to the unusual conditions of Mars than adults. If children go through puberty and its associated growth spurt on Mars, their bodies will be permanently tailored to it, unlike settlers who come over as adults.

You find other reasons for fear. First, there’s the radiation, against which Mars does not have a protective shield. And then there’s the low‐gravity environment, which would put children at high risk of developing deformities in their skeletons, hearts, eyes, and brains. Did the planners take this vulnerability of children into account? As far as you can tell, no.

So, would you let her go? Of course not. You realise this is a completely insane idea – sending children to Mars, perhaps never to return to Earth. The project leaders do not seem to know anything about child development and do not seem to care about children’s safety. Worse still: the company did not require proof of parental permission.

No company could ever take our children away and endanger them without our consent, or they would face massive liabilities. Right?

At the turn of the millennium, technology companies created a set of world-changing products that transformed life not just for adults all over the world but for children, too. Young people had been watching television since the 1950s but the new tech was far more portable, personalised and engaging than anything that came before. Yet the companies that developed them had done little or no research on the mental health effects. When faced with growing evidence that their products were harming young people, they mostly engaged in denial, obfuscation, and public relations campaigns. Companies that strive to maximise “engagement” by using psychological tricks to keep young people clicking were the worst offenders. They hooked children during vulnerable developmental stages, while their brains were rapidly rewiring in response to incoming stimulation. This included social media companies, which inflicted their greatest damage on girls, and video game companies and pornography sites, which sank their hooks deepest into boys. By designing a slew of addictive content that entered through kids’ eyes and ears, and by displacing physical play and in-person socialising, these companies have rewired childhood and changed human development on an almost unimaginable scale.

What legal limits have we imposed on these tech companies so far? Virtually none, apart from the requirement for children under 13 to get parental consent before they can sign a contract with a company. But the law in most countries didn’t require age verification; so long as a child checked a box to assert that she was old enough (or put in the right fake birthday), she could go almost anywhere on the internet – and sign into any social media app – without her parents’ knowledge or consent. (The law is being tightened in the UK, due to the 2023 Online Safety Act, and is under review in the US.)

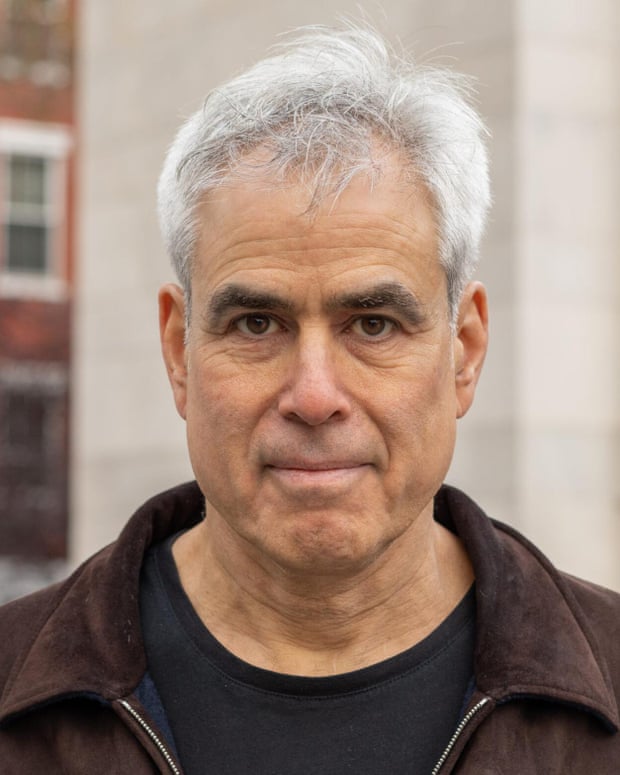

Profile

Jonathan Haidt

Show

Jonathan Haidt is a leading American social psychologist. He is professor of ethical leadership at the New York University Stern School of Business. Born in New York in 1963, he studied philosophy at Yale University and psychology at the Universities of Pennsylvania and Chicago. His books include The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom and The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion. His most recent title was the bestselling The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure, acclaimed in the New York Times and the Atlantic as a compelling, unprecedented, frightening analysis of how a generation of students has been politically and socially stunted by trigger warnings, cancel culture and a false and deepening belief in its own fragility.

Thus, the generation born after 1995 – gen Z – became the first generation in history to go through puberty with a portal in their pockets that called them away from the people nearby and into an alternative universe that was exciting, addictive and unstable. Succeeding socially in that universe required them to devote a large part of their consciousness to managing what became their online brand, posting carefully curated photographs and videos of their lives. This was now necessary to gain acceptance from peers, the oxygen of adolescence, and to avoid online shaming, the nightmare of adolescence. Gen Z teenagers got sucked into spending many hours of each day scrolling through the shiny happy posts of friends, acquaintances and distant influencers. They watched increasing quantities of user-generated videos and streamed entertainment, fed to them by algorithms that were designed to keep them online as long as possible. They spent far less time playing with, talking to, touching, or even making eye contact with their friends and families, thereby reducing their participation in social behaviour that is essential for successful human development.

The members of gen Z are, therefore, the test subjects for a radical new way of growing up, far from the real‐world interactions of small communities in which humans evolved. Call it the Great Rewiring of Childhood. It’s as if they became the first generation to grow up on Mars. And it has turned them into the Anxious Generation.

There was little sign of an impending mental illness crisis among adolescents in the 2000s. Then, quite suddenly, in the early 2010s, things changed. In just five years between 2010 and 2015, across the UK, the US, Canada, Australia and beyond, the number of young people with anxiety, depression and even suicidal tendencies started to rise sharply. Among US teenagers, those who reported experiencing a long period of feeling “sad, empty, or depressed” or a long period in which they “lost interest and became bored with most of the things they usually enjoy” – classic symptoms of depression – surged by roughly 150%. In other words, mental illness became roughly two and a half times more prevalent. The increases were similar for both sexes and happened across all races and social classes. And among a variety of mental health diagnoses, anxiety rates rose the most.

More recent data for 2020 was collected partly before and partly after the Covid shutdowns, and by then one out of every four American teen girls had experienced a major depressive episode in the previous year. Things got worse in 2021, but the majority of the rise was in place before the pandemic.

I addressed some of these issues in The Coddling of the American Mind, a book (about modern identity politics and hypersensitivity on university campuses) I wrote in 2017 with free speech campaigner Greg Lukianoff. The day after we published, an essay appeared in the New York Times with the headline: “The Big Myth About Teenage Anxiety.” In it, a psychiatrist raised several important objections to what he saw as a rising moral panic around teenagers and smartphones. He pointed out that most of the studies showing a rise in mental illness were based on “self‐reports”, which does not necessarily mean that there is a change in underlying rates of mental illness. Perhaps young people just became more willing to self‐diagnose or talk honestly about their symptoms? Or perhaps they started to mistake mild symptoms of anxiety for a mental disorder?

Was the psychiatrist right to be sceptical? He was certainly right that we need to look at multiple indicators to know if mental illness really is increasing. A good way to do that is to look at changes in figures not self‐reported by teens. For example, the number of adolescents brought in for emergency psychiatric care, or admitted to hospitals each year because they deliberately harmed themselves, either in a suicide attempt, or in what is called non‐suicidal self-injury, such as cutting oneself without the intent to die.

The rate of self‐harm for young adolescent girls nearly tripled from 2010 to 2020. The rate for older girls (ages 15–19) doubled, while the rate for women over 24 actually went down during that time. So whatever happened in the early 2010s, it hit preteen and young teen girls harder than any other group. Similarly, the suicide rate for young adolescents increased by 167% from 2010 to 2021.

The rapid increases in rates of self‐harm and suicide, in conjunction with the self‐report studies showing increases in anxiety and depression, offers a strong rebuttal to those who were sceptical about the existence of a mental health crisis. I am not saying that none of the increase in anxiety and depression is due to a greater willingness to report these conditions (which is a good thing) or that some adolescents began pathologising normal anxiety and discomfort (which is not a good thing). But the pairing of self‐reported suffering with behavioural changes tells us that something big changed in the lives of adolescents in the early 2010s.

Quick Guide

Anxiety: the numbers

Show

1 in 3

Proportion of British 18- to 24-year-olds now report recently experiencing depression or anxiety, compared with one in four in 2000.

250,000+

Number of children and young people in England are waiting for mental health support, meaning one in every 50 children is on the waiting list.

58%

Proportion of gen Z in the UK feel anxious frequently or all the time– a big jump from the one-third of gen X and one-quarter of baby boomers who said the same.

91%

Proportion of 18- to 24-year-olds report feeling stressed and not having a ‘good quality of life’.

100,000

One in eight young people aged 17-24 report having self-harmed last year and an estimated 100,000 people were admitted to hospital as a result of self-harm.

28%

Proportion of secondary school pupils in the UK stayed away from school last year owing to anxiety.

The arrival of the smartphone in 2007 changed life for everyone. Of course, teenagers had mobile phones since the late 1990s, but they were basic flip phones with no internet access, mostly useful for communicating directly with friends and family, one‐on‐one. Some adolescents had internet access via a home computer or laptop but it wasn’t till they got smartphones that they could be online all the time, even when away from home. According to a survey conducted by the US non-profit group Common Sense Media, by 2016, 79% of teens owned a smartphone, as did 28% of children between the ages of eight and 12.

As teenagers got smartphones, they began spending more time in the virtual world. A Common Sense report, in 2015, found that teens with a social media account reported spending about two hours a day on social media and around seven hours a day of leisure time online. Another 2015 report, by the Washington thinktank Pew Research, reveals that one out of every four teens said that they were online “almost constantly”. By 2022, that number had nearly doubled, to 46%. These “almost constantly” numbers are startling, and may be the key to explaining the sudden collapse of adolescent mental health. These extraordinarily high rates suggest that even when members of gen Z are not on their devices and appear to be doing something in the real world, such as sitting in class, eating a meal, or talking to you, a substantial portion of their attention is monitoring or worrying (being anxious) about events in the social metaverse. As the MIT professor Sherry Turkle wrote in 2015 about life with smartphones: “We are forever elsewhere.”

Faced with so many virtual activities, social media platforms and video streaming channels, many adolescents (and adults) lost the ability to be fully present with the people around them, which changed social life for everyone, even for the small minority that did not use these platforms. Social patterns, role models, emotions, physical activity, and even sleep patterns were fundamentally recast, for adolescents, over the course of just five years.

When I present these findings in public, someone often objects by saying something like: “Of course young people are depressed – just look at the state of the world in the 21st century. It began with the 9/11 attacks, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the global financial crisis. They’re growing up with global warming, school shootings in the US and elsewhere, political polarisation, inequality, and ever-rising student loan debt. Not to mention wars in Ukraine and the Middle East.”

But while I agree that the 21st century is off to a bad start, the timing does not support the argument that gen Z is anxious and depressed because of rising national or global threats. Even if we were to accept the premise that the events from 9/11 through to the global financial crisis had substantial effects on adolescent mental health, they would have most heavily affected the millennial generation (born between 1981 and 1995), who found their world shattered and their prospects for upward mobility reduced. But this did not happen; their rates of mental illness did not worsen during their teenage years. Also, had the financial crisis and other economic concerns been major contributors, adolescent mental health would have plummeted in 2009, the darkest year of the financial crisis, and it would have improved throughout the 2010s as the unemployment rate fell, the stock market rose, and the global economy heated up.

There is just no way to pin the surge of adolescent anxiety and depression on any economic event or trend that I can find.

When Covid arrived in 2020, the disease and the lockdowns made sociogenic illness more likely among people of any age. Covid was a global threat and a stressor. The lockdowns led teens to spend even more time on social media, especially TikTok, which was relatively new. But the steep rise in anxiety and depression among adolescents was in place well before the pandemic.

The other explanation I often hear is that gen Z is anxious and depressed because of climate change, which will affect their lives more than those of older generations. Their concern is legitimate, but impending threats to a nation or generation (as opposed to an individual) do not historically cause rates of mental illness to rise. When countries are attacked, either by military force or by terrorism, citizens usually rally around the flag and one another. They are infused with a strong sense of purpose and suicide rates drop. When young people rally together around a political cause, from opposing the Vietnam war in the 1960s through peak periods of earlier climate activism in the 1970s and 1990s, they become energised, not dispirited or depressed.

People don’t get depressed when they face threats collectively; they get depressed when they feel isolated, lonely, or useless.

Parents I talk to about smartphones, social media and video games tell stories of “constant conflict”. They try to lay down rules and enforce limits, but there are so many arguments about why a rule needs to be relaxed, and so many ways around the rules, that family life all over the world has come to be dominated by disagreements about technology. Maintaining family rituals such as mealtimes can feel like resisting an ever-rising tide.

A mother I spoke with in Boston told me about the efforts she and her husband had made to keep their 14- year-old daughter, Emily, away from Instagram. They could see the damaging effect it was having on her. To curb her access, they tried various ways to monitor and limit the app on her phone. However, life became a permanent struggle in which Emily eventually found ways around the restrictions. In one episode, she got into her mother’s phone, disabled the monitoring software, and threatened to kill herself if her parents reinstalled it. Her mother told me:

“It feels like the only way to remove social media and the smartphone from her life is to move to a deserted island. She attended summer camp for six weeks each summer where no phones were permitted – no electronics at all. When we picked her up from camp she was her normal self. But as soon as she started using her phone again it was back to the same agitation and glumness.”

Platforms such as Instagram – where users post content about themselves, then wait for the judgments and comments of others, and the social comparison that goes with it – have larger and more harmful effects on girls and young women than on boys and young men. The more time a girl spends on social media, the more likely she is to be depressed or anxious. Girls who say that they spend five or more hours each weekday on social media are three times as likely to be depressed as those who report no social media time. The difference is far less marked with boys. Girls spend more time on social media, and the platforms they are on – particularly Instagram and Snapchat – are the worst for mental health. A 2017 study in the UK asked teenage girls to rate the effects of the most popular social media platforms on different parts of their wellbeing, including anxiety, loneliness, body image, and sleep. Teenagers rated Instagram as the worst of the big five apps, followed by Snapchat. YouTube was the only platform that received a positive overall score.

The 2021 song Jealousy, Jealousy by Olivia Rodrigo sums up what it’s like for many girls to scroll through social media today. The song begins: “I kinda wanna throw my phone across the room/ ’Cause all I see are girls too good to be true.” Rodrigo then says that “co-comparison” with the perfect bodies and paper-white teeth of girls she doesn’t know is slowly killing her.

Psychologists have long studied social comparison and its pervasive effects. The American social psychologist Mark Leary says it’s as if we all have a “sociometer” in our brains – a gauge that runs from nought to 100, telling us where we stand in the local prestige rankings. When the needle drops, it triggers an alarm – anxiety – that motivates us to change our behaviour and get the needle back up. So what happened when most girls in a school got Instagram and Snapchat accounts and started posting carefully edited highlight reels of their lives and using filters and editing apps to improve their virtual beauty and online brand? Many girls’ sociometers plunged, because most were now below what appeared to them to be the average. All around the developed world, an anxiety alarm went off in girls’ minds, at approximately the same time.

A 13-year-old girl on Reddit explained how seeing other girls on social media made her feel, using similar words to Olivia Rodrigo:

i cant stop comparing myself. it came to a point where i wanna kill myself cause u dont want to look like this and no matter what i try im still ugly/feel ugly. i constantly cry about this. it probably started when i was 10, im now 13. back when i was 10 i found a girl on tiktok and basically became obsessed with her. she was literally perfect and i remember being unimaginably envious of her. throughout my pre-teen years, i became “obsessed” with other pretty girls.

Instagram’s owner, Facebook (now Meta), itself commissioned a study on how Instagram was affecting teens in the US and the UK. The findings were never released, but whistleblower Frances Haugen smuggled out screenshots of internal documents and shared them with reporters at the Wall Street Journal. The researchers found that Instagram is particularly bad for girls: “Teens blame Instagram for increases in the rate of anxiety and depression… This reaction was unprompted and consistent across all groups.”

If we confine ourselves to examining data about depression, anxiety, and self-harm, we’d conclude that the Great Rewiring has been harder on girls than on boys. But there’s plenty of evidence that boys are suffering too.

A key factor was boys taking up online multiplayer video games in the late 2000s and smartphones in the early 2010s, both of which pulled them decisively away from face-to-face or shoulder-to-shoulder interaction. At that point, I think we see signs of a “mass psychological breakdown”. Or, at least, a mass psychological change. Once boys had multiple internet-connected devices, many of them got lost in cyberspace, which made them more fragile, fearful, and risk averse on Earth. Beginning the early 2010s, boys across the western world began showing concerning declines in their mental health. By 2015, a staggering number of them said that they had no close friends, that they were lonely, and that there was no meaning or direction to their lives.

The overwhelming feeling I get from the families of both boys and girls is that they are trapped and powerless in the face of the biggest mental health crisis in history for their children. What should they – what should we – do?

When I say that we need to delay the age at which children get smartphones and social media accounts, the most common response is: “I agree with you, but it’s too late.” It has become so ordinary for 11-year-olds to walk around staring at their phones, swiping through bottomless feeds, that many people cannot imagine that we could change it if we wanted to. “That ship has sailed,” they tell me.

Yet we are not helpless. It often feels that way because smartphones, social media, market forces, and social influence combine to pull us into a trap that social scientists call a collective action problem. Children starting secondary school are trapped in a collective action problem when they arrive for their first day and see that some of their classmates have smartphones and are connecting on Instagram and Snapchat, even during class time. That puts pressure on them to get a smartphone and social media as well.

It’s painful for parents to hear their children say: “Everyone else has a smartphone. If you don’t get me one, I’ll be excluded from everything.” Many parents therefore give in and buy their child a smartphone at age 11, or younger. As more parents relent, pressure grows on the remaining kids and parents, until the community reaches a stable but unfortunate equilibrium: Everyone really does have a smartphone.

How do we escape from these traps? Collective action problems require collective responses: parents can support one another by sticking together. There are four main types of collective response, and each can help us to bring about major change:

1. No smartphones before year 10

Parents should delay children’s entry into round-the-clock internet access by giving only basic phones with limited apps and no internet browser before the age of 14.

2. No social media before 16

Let children get through the most vulnerable period of brain development before connecting them to an avalanche of social comparison and algorithmically chosen influencers.

3. Phone-free schools

Schools must insist that students store their phones, smartwatches, and any other devices in phone lockers during the school day, as per the new non-statutory guidance issued by the UK government. That is the only way to free up their attention for one another and for their teachers.

4. Far more unsupervised play and childhood independence

That’s the way children naturally develop social skills, overcome anxiety, and become self-governing young adults.

These four reforms are not hard to implement – if many of us do them at the same time. They cost almost nothing. They will work even if we never get help from our legislators or from the tech giants, which continue to resist pressure to protect young users’ safety and wellbeing. If most of the parents and schools in a community were to enact all four, I believe they would see substantial improvements in adolescent mental health within two years. Given that AI and spatial computing (such as Apple’s new Vision Pro goggles) are about to make the virtual world far more immersive and addictive, I think we’d better start today.